Οὕτως ἡμᾶς λογιζέσθω ἄνθρωπος ὡς ὑπηρέτας Χριστοῦ καὶ οἰκονόμους μυστηρίων θεοῦ. ὧδε λοιπὸν ζητεῖται ἐν τοῖς οἰκονόμοις, ἵνα πιστός τις εὑρεθῇ. ἐμοὶ δὲ εἰς ἐλάχιστόν ἐστιν, ἵνα ὑφʼ ὑμῶν ἀνακριθῶ ἢ ὑπὸ ἀνθρωπίνης ἡμέρας· ἀλλʼ οὐδὲ ἐμαυτὸν ἀνακρίνω. οὐδὲν γὰρ ἐμαυτῷ σύνοιδα, ἀλλʼ οὐκ ἐν τούτῳ δεδικαίωμαι, ὁ δὲ ἀνακρίνων με κύριός ἐστιν. ὥστε μὴ πρὸ καιροῦ τι κρίνετε ἕως ἂν ἔλθῃ ὁ κύριος, ὃς καὶ φωτίσει τὰ κρυπτὰ τοῦ σκότους καὶ φανερώσει τὰς βουλὰς τῶν καρδιῶν· καὶ τότε ὁ ἔπαινος γενήσεται ἑκάστῳ ἀπὸ τοῦ θεοῦ. (1 Corinthians 4:1–7)

“Think of us in this way, as servants of Christ and stewards of God’s mysteries. Moreover, it is required of stewards that they be found trustworthy. But with me it is a very small thing that I should be judged by you or by any human court. I do not even judge myself. I am not aware of anything against myself, but I am not thereby acquitted. It is the Lord who judges me. Therefore do not pronounce judgment before the time, before the Lord comes, who will bring to light the things now hidden in darkness and will disclose the purposes of the heart. Then each one will receive commendation from God.” (NRSV)

Paul. Apollos. Working in the same enterprise, with the same aim. Probably with very different styles. Do they rub each other the wrong way? Do they resent each other? Does one of them try to outdo the other? Others, at least, treat them as rivals, lining up as fans or critics of one or the other.

What will Paul say? He says: we are stewards. What we are working with—our message, and the resources we muster for conveying that message—is not our own. It belongs to another. What is required of us is faithfulness to the one we are working for.

Paul and his coworker Apollos seem to be at odds in some way. This puts a kink in the works. It raises many questions. But in this moment Paul answers none of the questions swirling around Corinth. Perhaps he was not able. But also, he thinks it is better to refocus attention on another question. One question. Only one. Am I being faithful to the one who has entrusted me with this work in which I am engaged?

Well, who is to make that determination?

And here we get the astonishing mixture of confidence and diffidence, self-assurance and self-deprecation, that is characteristic of Paul. With bold defiance he tells his readers: if you make a determination, if you judge, I do not care about your finding. You are not my judge. Your judgment counts for nothing.

But immediately also this: I also am not my own judge. As far as I know, I am in the right—I am a faithful steward. But my knowledge, including especially my self-knowledge, is limited. So my judgment also counts for nothing.

And as for judging Apollos—Paul doesn’t even go there.

Who can judge, then? Who can evaluate Paul? And who can evaluate his coworker? (Whom he refuses to speak of as a pain in the ass, or as a rival, or even as by rights a subordinate, though, reading between the lines, we may well deem him to have been all three.) Only the Lord can judge. Only the Lord can shed light on all that is hidden in the dark places of the human heart, and in the pressing case before us now the Lord is not yet doing that. We expect that revelation in the future.

Paul, interjecting his one question, and declining to answer it in his own case, and in the case of Apollos, warns us gently not to answer it quickly in our own case either, and at the same to bear in mind that someday someone else who sees all clearly will answer it.

So we must suspend judgment.

What a stunningly disappointing and useless answer! We demand a verdict! Justify yourself, Paul! He replies: I can’t do that. —Then give us your assessment of Apollos! He replies: I can’t do that either.

What strange paralysis is this? Strange because on other occasions, facing other questions, discussing other problematic persons under different circumstances, this most verbose of apostles renders definite verdicts, clear directives, at some length, and even with some heat. But faced with a negative review of his own performance, and challenged to stand up for himself against rivals—rivals he believes to be working in the same cause, even though not in his own style, but on a common basis—nothing. No verdict. He drops one question, refuses to answer it, and begs off.

Pitiful, no? Perhaps even despicable?

Or:

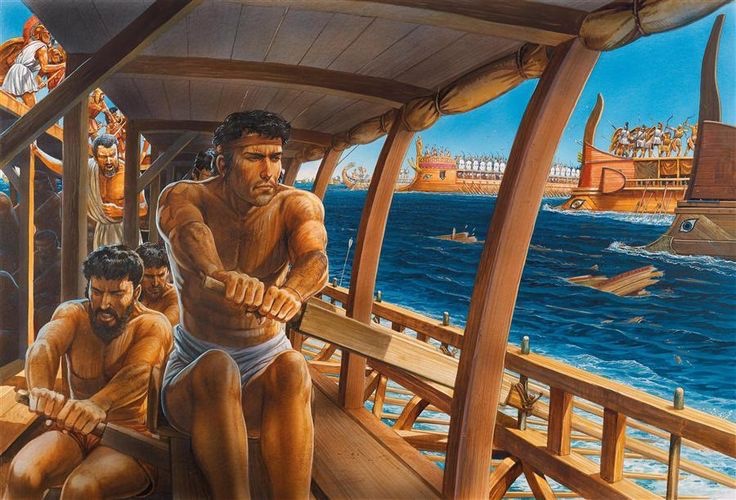

What would our (work-) life be like, and how fruitful could we be, if we learned to suspend judgment indefinitely in matters in which circumstances or people set us at odds with those with whom we are meant to be toiling toward a shared end? What if we refused to condemn or justify ourselves or them, and managed not to care about praise or blame from others, and just kept our hands on the oars?

καὶ κοπιῶμεν ἐργαζόμενοι ταῖς ἰδίαις χερσίν· λοιδορούμενοι εὐλογοῦμεν, διωκόμενοι ἀνεχόμεθα, δυσφημούμενοι παρακαλοῦμεν. (1 Corinthians 4:12–13)

“We grow weary from the work of our own hands. When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; when slandered, we speak kindly.” (NRSV)

Imagine that.