By long tradition the book of Psalms in the Hebrew scriptures is attributed to King David, the “man after God’s own heart” who reunited and governed the twelve tribes after the death of Saul, Israel’s failed first king, a mentally ill man whose derangement issued in disobedience to God, overreach with regard to his own authority, defeat in battle, and death by his own sword.

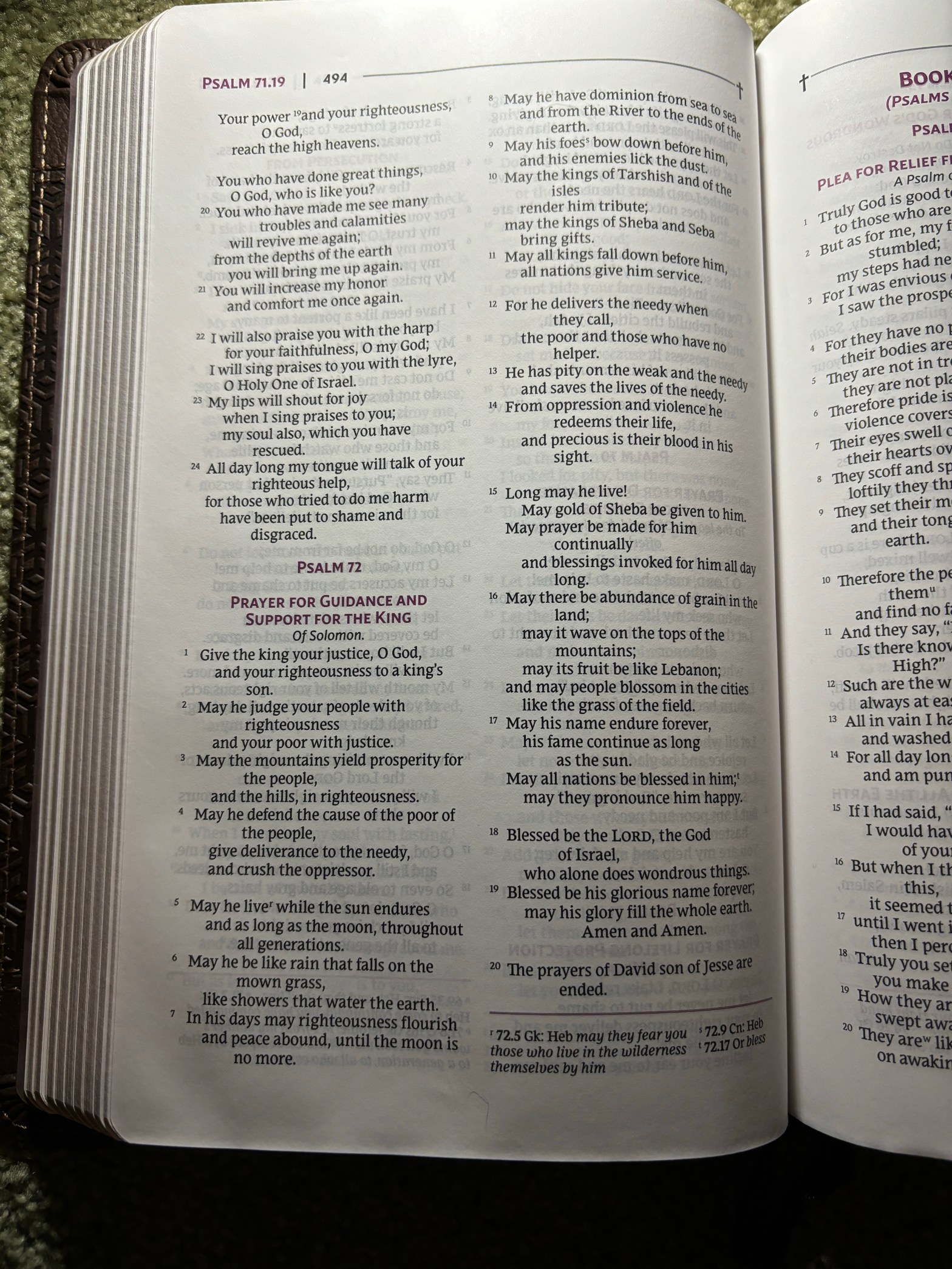

Historians doubt that any of the biblical psalms were written by a king named David. What casual readers of the Bible do not notice is that the text of the Psalter itself denies that David wrote Psalms 73 through 150: notice verse 20 of Psalm 72: “The prayers of David son of Jesse are ended.” Where David appears in the headings of the remaining Psalms—for example, Psalm 110—the implication is that the psalm is about him, not by him. But the implication is that Psalm 72 and earlier Psalms are by David.

The headings of the psalms were self-evidently written by a later editor, not by whoever wrote each psalm, and the same is surely true of 72:20. Nevertheless, it says what it says, and it is part of the canonical text of scripture. So in reading the Psalms as scripture, we must at least pay some attention to these editorial markers.

So, among the various angles from which we must meditate on the text of Psalm 72, we must ask: how does it read if we consider it as a prayer uttered by King David? And also: how does it read if we consider it as a prayer by King David for his son and successor Solomon? —because its heading says “of Solomon” (Hebrew: le-Schlomo, which could conceivably mean “by Solomon” but since verse 20 says “the prayers of David are ended” must mean “for Solomon”).

Read in this way, Psalm 72 stands as an expression by Israel’s first God-blessed king—the central hero of Israel’s golden age, King David, who was also the focus of later (kingless and exiled) Israel’s hope for restoration of divine rule through a royal messiah—of Israel’s desire for good governance.

Because—it is unavoidable, if you read the content of the prayer—this psalm is all about just and righteous governance. OK, it is also about longevity (72:5–7, “May he live while the sun endures . . .”) and hegemony (72:8–11 (“May he have dominion from sea to sea and from the River to the ends of the earth”), and also prosperity (72:16, “May there be abundance of grain”). But the petitions for longevity and hegemony, and even more the petition for prosperity, are subordinated to the theme announced in the first petition (72:1–2: “Give the king your justice, O God, and your righteousness to a king’s son. May he judge your people with righteousness and your poor with justice”).

And these subordinate petitions, and even the opening petition for just and righteous rule for Israel, are by the end of the psalm subordinated further to the closing, universalizing petitions, which are grounded in the promise to Abraham. And that promise to Abraham, made centuries earlier, is this: “In you all families of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 12:3). The closing petitions of Psalm 72, which invokes God’s blessing on the Israelite (and so ultimately Abrahamic) king, are therefore: “May all nations be blessed in him” (72:17) and “Blessed be the LORD [here the Hebrew text has the divine name given to Moses from the burning bush], the God of Israel . . . may his glory fill the whole earth” (72:18–19).

That universal promise is the basis of this psalm, this prayer, this manifesto. And what is its content? In other words, how will God’s blessing on the Israelite king lead to blessing for “all nations,” for “the whole earth”? What, in this vision, will lead the rulers of foreign peoples to bow before the Israelite king and offer him their service (72:11)? What is the achievement that will mark this Israelite king—David, or Solomon, or any later king, or any later government that seeks to restore the nation and the government that were ordained and blessed by God in Israel’s golden age? This, and only this:

For he delivers the needy when they call,

Psalm 72:12–14

the poor and those who have no helper.

He has pity on the weak and the needy

and saves the lives of the needy.

From oppression and violence he redeems their life,

and precious is their blood in his sight.

The true Israelite king, from his residence on holy Mount Zion, will care most about these things. And the clear implication, here and in every biblical passage setting forth the constitution of Zion, is that the true Israelite king will accomplish these things not only for members of his own family, or only for members of his own nation, but for all nations, for the whole earth.

So I ask you: can any regime that calls itself Zion, but is not centrally focused on delivering from oppression, violence, and bloodshed the poor and needy—not only Israelites but the needy of every family and tribe—lay honest claim to that name?

Zion is a holy name. It names a place on earth that is entirely open to heaven, a portal through which the goodness of heaven can flow down to flood the whole earth. Zion is the place where divine righteousness is perfectly tempered with divine mercy. Zion is the original and archetypal city on a hill, to whose light all peoples will be drawn.

Zion is a city whose constitution and governors honor and enact the final prayer of its archetypal king.

Conflicting voices today demand that I either endorse or denounce Zionism. It seems to me that, as with so many other good words, adding in -ism to Zion perverts and profanes the spirit of the thing and hardens its living heart into a dead bone of contention.

Zion I know, though only as a rumor, a promise, a hope, a prayer. Zion I long for. Oh, to be a citizen of Zion! But what is this Zionism that demands either my loyalty or my denunciation? Ask me to declare myself a Zionist when you can show me Zion. I am not seeing it anywhere.

The foregoing is a meditation on Psalm 72. Here is the psalm, in the NRSVue, from BibleGateway.

1 Give the king your justice, O God,

and your righteousness to a king’s son.

2 May he judge your people with righteousness

and your poor with justice.

3 May the mountains yield prosperity for the people,

and the hills, in righteousness.

4 May he defend the cause of the poor of the people,

give deliverance to the needy,

and crush the oppressor.

5 May he live while the sun endures

and as long as the moon, throughout all generations.

6 May he be like rain that falls on the mown grass,

like showers that water the earth.

7 In his days may righteousness flourish

and peace abound, until the moon is no more.

8 May he have dominion from sea to sea

and from the River to the ends of the earth.

9 May his foes bow down before him,

and his enemies lick the dust.

10 May the kings of Tarshish and of the isles

render him tribute;

may the kings of Sheba and Seba

bring gifts.

11 May all kings fall down before him,

all nations give him service.

12 For he delivers the needy when they call,

the poor and those who have no helper.

13 He has pity on the weak and the needy

and saves the lives of the needy.

14 From oppression and violence he redeems their life,

and precious is their blood in his sight.

15 Long may he live!

May gold of Sheba be given to him.

May prayer be made for him continually

and blessings invoked for him all day long.

16 May there be abundance of grain in the land;

may it wave on the tops of the mountains;

may its fruit be like Lebanon;

and may people blossom in the cities

like the grass of the field.

17 May his name endure forever,

his fame continue as long as the sun.

May all nations be blessed in him;

may they pronounce him happy.

18 Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel,

who alone does wondrous things.

19 Blessed be his glorious name forever;

may his glory fill the whole earth.

Amen and Amen.

20 The prayers of David son of Jesse are ended.