I work in book publishing. Every book we publish has a title. Sometimes we have fun titling them. One way publishers have fun with titles is by using ‑ing words ambiguously. Take the title Redeeming Transcendence in the Arts. Is “redeeming” a gerund, so that the suggestion is that people should redeem transcendence? Or is it a participle used attributively, suggesting that transcendence exercises a redeeming role? Does the title Loving Wisdom suggest that this book will persuade us that we should love wisdom and show us how? Or is it going to tell us about a wisdom (divine Wisdom?) whose character is loving? Will a book titled Nurturing Faith tell us how to nurture faith in people, or will it suggest that faith itself has hurturing properties? We must read to find out.

So in the title of this post, Inviting Jesus? Is someone going to invite Jesus to do something, or to be somewhere? Or is Jesus the one who does the inviting? Is “inviting” a descriptor of the character of Jesus?

Yes.

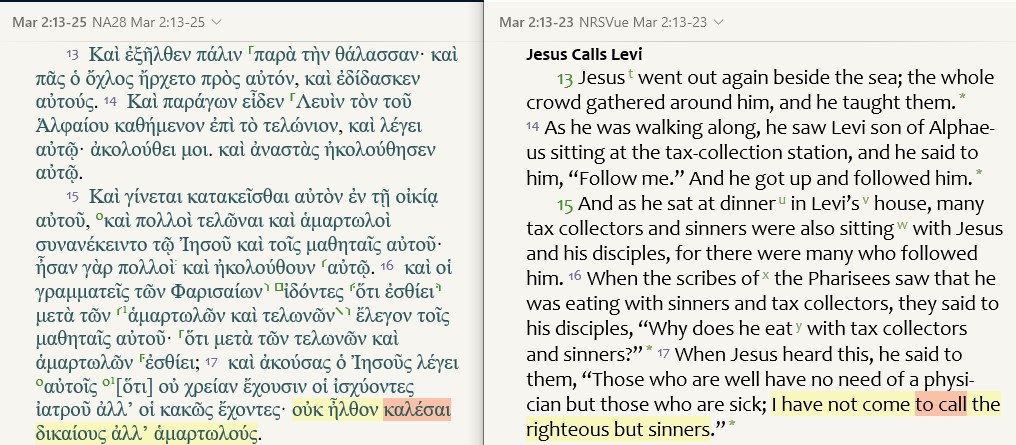

The NRSVue heading for Mark 2:13–17 is “Jesus Calls Levi.” This is because Jesus says to Levi, “Follow me.” The text does not say that Jesus “calls” Levi, but it shows Jesus doing just that. And then in verse 17, Jesus says that he has come to “call” not the righteous but sinners. So it seems Jesus is doing the calling.

But the Greek verb kaleō, here translated “call” in the NRSVue, is often more naturally rendered “invite.” If asked what Jesus said about calling, many of us would think immediately of his enigmatic and disturbing “Many are called, but few are chosen” (Matthew 22:14; πολλοὶ γάρ εἰσιν κλητοί, ὀλίγοι δὲ ἐκλεκτοί). This saying wraps up his story (parable) about a king who invites many guests to his son’s wedding feast. In 22:3 the king “sent his slaves to call those who had been invited to the wedding banquet” (NRSVue, with emphasis added). But “call” and “invite” are here translating the same Greek verb, kaleō (καὶ ἀπέστειλεν τοὺς δούλους αὐτοῦ καλέσαι τοὺς κεκλημένους). So the slaves are sent to call those who have already been called, or to invite those who have already been invited. But they decline to come. Jesus interprets their refusal by saying that they were not chosen (elect, ἐκλεκτοί).

Back to the story of Levi in Mark 2. Who is doing the inviting in this story? If we look closely, we see that it is an invitation sandwich. Jesus kicks things off by inviting Levi to follow him. And Jesus wraps things up by referring to telling us who he has come to invite. But in between: it seems that someone else has invited Jesus! Because in verse 15 we see Jesus reclining (to eat) in Levi’s house.

(Here, as happens often in the Gospels, Mark is less than carefully explicit in saying exactly who does what. In “he got up and followed him” [καὶ ἀναστὰς ἠκολούθησεν αὐτῷ] it’s clear enough from the context that Levi got up and followed Jesus. But then “and it happened that he reclined in his house” [γίνεται κατακεῖσθαι αὐτὸν ἐν τῇ οἰκίᾳ αὐτοῦ] it is unclear grammatically who is which he. NRSVue decides we need some help and make “his house” into “Levi’s house.” This is surely correct.)

So the invited becomes the inviter. And this is the point, is it not? Jesus invites, and Jesus wants to be invited in return. The whole point of an invitation is to stimulate reciprocity and thereby to establish a relationship.

But the thing that first grabbed my attention when I read this little story this morning was something else, something that it does not say, and more specifically, something that Jesus does not say. When Jesus says “I came to call sinners,” wouldn’t we expect him to add “to repentance” (εἰς μετάνοιαν)?

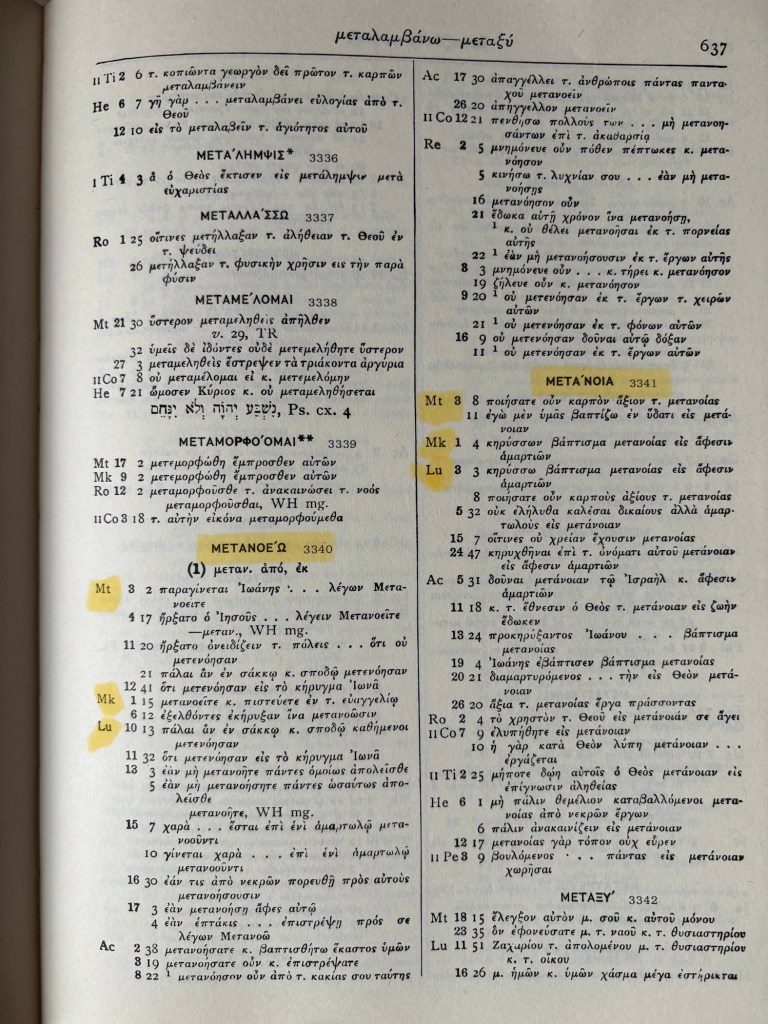

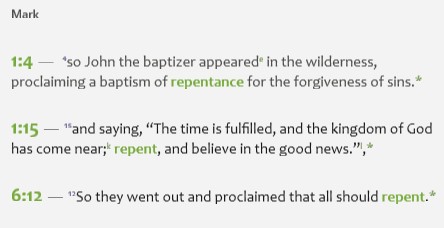

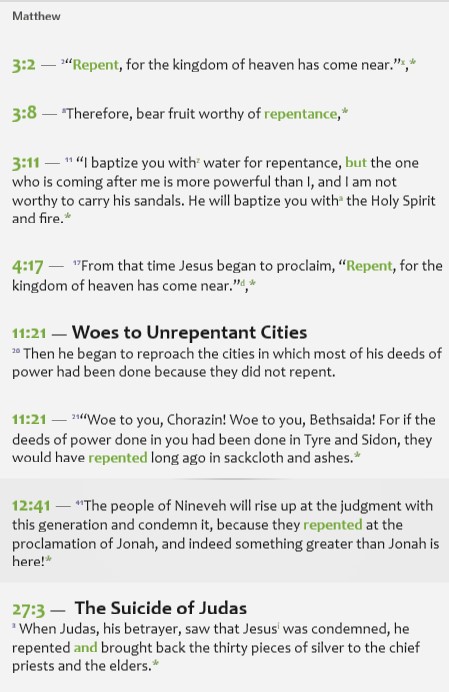

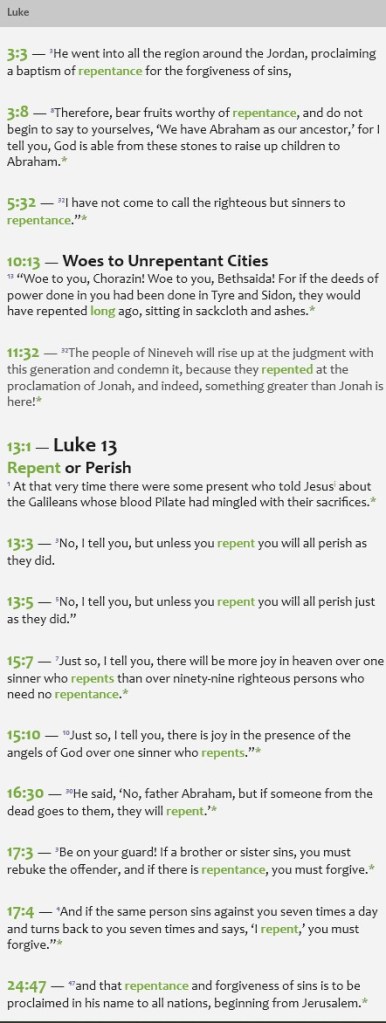

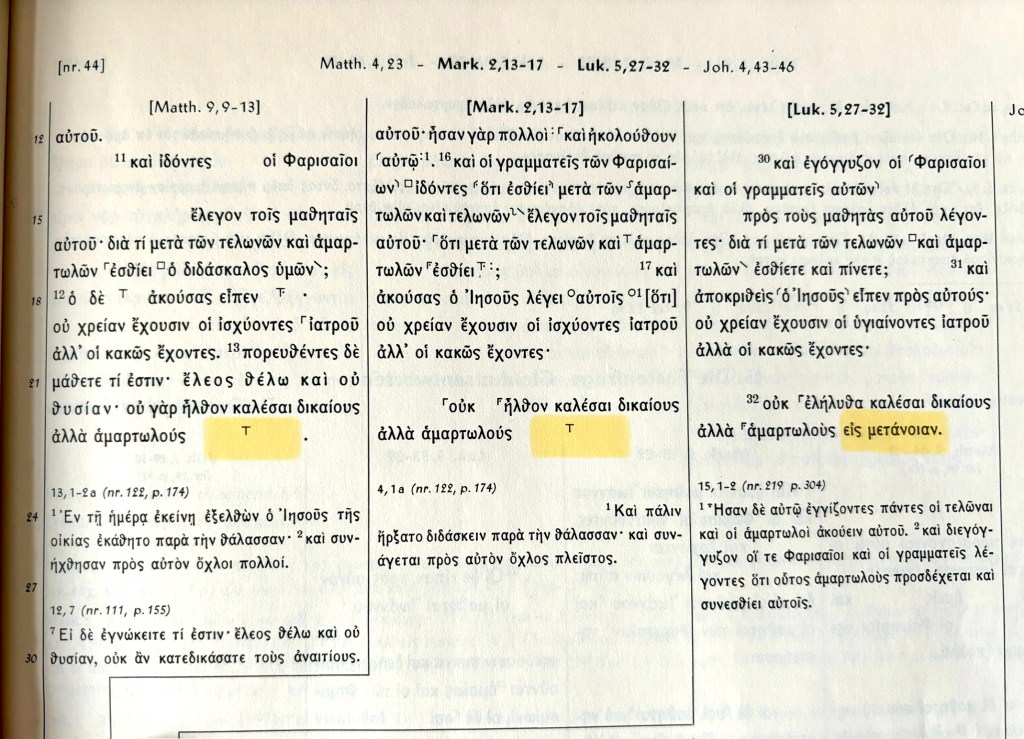

Maybe I was expecting those two words, and missed them, because somewhere in the back of my head I was remembering Luke’s version of this story (in Luke 5:27–32). From all that we see in the differences between Mark and Luke, and Mark and Matthew, it appears that Mark was written first, and that Luke and Matthew both modify Mark in places. In this passage, Luke removes Mark’s potential ambiguity as to whether the house in which the meal takes belongs to Levi or to Jesus: Luke says “Then Levi gave a great banquet for him in his house” (Luke 5:29). And Luke also adds the words “to repentance” (εἰς μετάνοιαν) to make clear the intent of Jesus’s invitation to sinners. Neither Mark 2:17 nor Matthew 9:13 has those words. The highlighting in figure 2 makes this clear. Those little sigla in Matthew and Mark point to notes which tell us that in numerous later manuscripts of of those two gospels scribes inserted those two words (perhaps because they remembered them from Luke), but in the earlier manuscripts of Mark they are not present.

Now, Mark is not allergic to repentance. He knows that John the Baptist proclaimed a baptism for repentance unto the forgivness of sins (Mark 1:4, 15), and he knows that when Jesus sent out the Twelve, they “proclaimed that all should repent” (Mark 6:12). But would you have guessed that those are the only two instances in which the Gospel of Mark mentions repentance?

Matthew, apart from the preaching of John the Baptist, says that Jesus repeated John the Baptist’s call to repentance (Matthew 4:17), and that he complained about the fact that various cities in which he had preached did not repent (Matthew 11:21, 12:41), but that’s all for Matthew. The Gospel of John does not mention repentance at all. Luke is the gospel in which repentance is a recurring theme. (See figures 3–6 below for concordance views.)

And nowhere in the gospels, in his individual encounters with persons of all types (followers, seekers, sinners, challengers, accusers), does Jesus ever tell a single of them to repent. According to Matthew and Luke, he tells large audiences to repent. But never an individual. The call to repent comes in speeches, not in conversation.

In converations, Jesus invites.

What to make of this? Who am I to say? This is not a pastoral instruction (not my place) or a research paper (I don’t have time). I have just been reflecting on something that I noticed in reading a passage in Mark 2 this morning, and I looked up a couple of things with the help of electronic and print concordances. You should look closely to see whether I have missed something, and please let me know if I have.

I do not want to be misunderstood. The church through the ages has taught that repentance is an essential stage in the path to salvation, and it has grounded this teaching in Scripture. This teaching stands, and it will stand.

But in our current cultural setting, everyone who has eyes to see and ears to hear knows that the church itself—Christians themselves—have much to repent of. Perhaps here and there we see some Christians heeding Martin Luther’s first thesis, that “Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ in saying ‘Do penance’ willed that the entire life of the faithful should be penance,” and Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s insight that when Jesus Christ calls a person, he calls that person to come and die (i.e., to repent so comprehensively as to give over their whole life to God). But for the most part, I fear that when the general population around us hears the Christian church exhort the sinners of the world to repent, what the world hears is sanctimony and hypocrisy. And they are not necessarily hallucinating. These things may really be there. So Christians possessing a modicum of self-awareness are slow to say anything about the need for the world around us to repent.

That is understandable. And it is regrettable. And it is not what I am getting from the foregoing meditation.

What I am suggesting is that the Jesus of the gospels, to the extent that he gives us a pattern for our own conversation and conduct vis-à-vis inviduals who are not already his followers, seems not to want us to begin by telling them that they need to repent. He seems to want us to invite them, to welcome them, and to do so in ways that encourage them to invite and welcome us as well, and he wants us to accept their hospitality graciously when they do. As for what will follow—well, we will see. We will see what God will do. We will see who the chosen are. And we may expect that the chosen will turn out to be simply sinners who were grateful to be invited.

We are to invite, and to offer a Jesus who invites: an inviting Jesus.